Shechem: Insights From Biblical Geography

In my previous two posts (here and here), I have sought to demonstrate how learning biblical geography can be a helpful way of studying the text of Scripture. The ancient city of Shechem, located near modern Nablus, is another example of what can be learned by studying biblical geography. The city of Shechem is mentioned 54 times in the OT, not counting an additional 13 times where it refers to an individual by the same name. It is specifically mentioned twice in the NT (both in Acts 7:16), however, the mention of Sychar in John 4 may be the same city. It is certainly the same geographical area (see discussion below). Because of its frequency, we will only examine the most significant occurrences of this city in Scripture.

Shechem and the Patriarchs

The first mention of Shechem occurs in Genesis 12:6 when Abram enters the land of Canaan. We’re told that the Lord appeared to Abram and promised him that the Land of Canaan would be given to his descendants. As a result Abram built an altar. Thus our initial introduction to Shechem involves the Lord revealing Himself to Abram and Abram’s grateful response by building an altar.

Shechem plays a significant role in the story of Jacob after his return to the land (having spent 20 years with his uncle Laban in Haran). It is only the second place in Canaan where one of the patriarchs purchased a part of the land (the other was the cave of Macpelah and surrounding land where Abraham buried Sarah–Gen. 23:16-20). We are told that Jacob purchased some land near Shechem, and then, like his grandfather Abram, he built an altar there which he called “El Elohe Israel” (God, the God of Israel–Gen. 33:18-20). Thus, the first two mentions of Shechem in the Bible represent God’s promise of the land, along with Jacob’s purchase of some of that land, followed by both patriarchs worshipping the true God by building an altar to Him.

Things take a turn for the worse, however, when Jacob’s daughter Dinah is raped by a man named Shechem (Gen. 34). Shechem was the son of Hamor, the ruler of the city at this time, and for whom, apparently, the city was named. Outraged at the treatment of their sister, the brothers (led by Simeon and Levi) devise a plan that leads to the destruction of the people of Shechem. Jacob fears retaliation by the surrounding inhabitants and God appears to him at that time telling him to go to Bethel. Before leaving, however, Jacob has his household put away all their foreign gods and purify themselves (Gen. 35:2).

As an interesting sidenote: In Hebrew the name “Hamor” means “donkey.” The inhabitants of Shechem are referred to as the “sons of Hamor” or “sons of a donkey.” While excavating the city under the lowest floor of the outer guardroom, what appears to be a donkey was found buried there [Toombs, L. E. (1992). Shechem (Place). In D. N. Freedman (Ed.), The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary (Vol. 5, p. 1182)]. The reason this is interesting is that Canaanites are known to have ritually slaughtered donkeys in dedication to their gods and buried them in the foundation of the city gates. See the following article: Bronze-Age Donkey Sacrifice Found in Israel.

Joshua

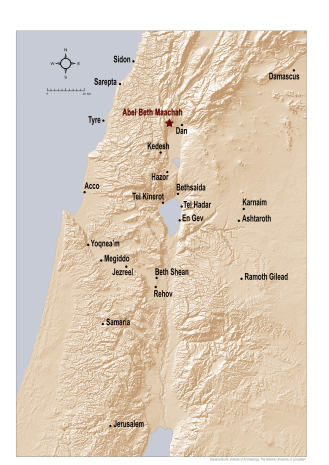

The Book of Joshua informs us that Shechem was both a city of refuge (Josh. 20:7), as well as a Levitical city (Josh. 21:21). Shechem was located near two mountains–Gerizim and Ebal. Before entering the Promised Land, Moses had commanded the people to build an altar on Mount Ebal and to divide the tribes between the two mountains. Half were to pronounce the blessings of the Law from Mount Gerizim, while the other half were to pronounce the curses of the Law from Mount Ebal. The fulfillment of this command is recorded in Joshua 8:30-35. Shechem is also the setting for Joshua’s famous speech that includes the words, “Choose for yourselves this day whom you will serve. . . But as for me and my house, we will serve the Lord” (Josh. 24:15; see Josh. 24:1). These important events recall the patriarchal stories, especially the story of Jacob. Just as Jacob had called on his household to put away their foreign gods, so Joshua, centuries later, challenged the nation of Israel to do the same. Except for the horrendous crime committed by Jacob’s sons in the slaughter of the people of Shechem, its early history left a legacy of commitment to God and a repudiation of foreign gods. Shechem was also the place where the bones of Joseph were laid to rest (Josh. 24:32), a reminder of the promise given to Abram at Shechem that God would give his descendants the Land of Canaan. Not too bad of a start for this geographical location. But all that was about to change!

Abimelech

The story of Abimelech, the son of Gideon by a concubine, is recorded in Judges 8:30-9:57. Although at one point Gideon had broken down the altar of Baal and cut down the Asherah pole (Judg. 6:27-28), leading Israel away from idolatry, by the end of his life he was responsible for leading Israel back into idolatry. Abimelech’s mother was from Shechem (Judg. 8:31) and he was able to convince the leaders of Shechem to make him king (Judg. 9:1-2) and destroy the other sons of Gideon (also known as Jerubaal). Abimelech hires 70 “worthless men” to do the job of slaughtering the 70 sons of Gideon. He hires them by using money from the temple in Shechem dedicated to the god Baal-Berith (Judg. 9:4-6). It is unclear how many temples existed in Shechem. Later in the story a temple dedicated to El-Berith is also mentioned (Judg. 9:46). Many scholars believe that these are two names for the same temple. El, which means god (or God), was the head of the Canaanite pantheon. According to Canaanite religion, Baal was a son (or possibly a grandson). There is also a sanctuary mentioned in Joshua 24:26. After Joshua wrote some words in the book of the Law, we are told that he set up a large stone “under the oak that was by the sanctuary of the Lord.” Ironically, this may be the same place later called the temple of Baal-Berith. In other words, a place that was known for turning from foreign gods to worship the true God had become a place where Baal was now worshipped. Another irony of the Abimelech story is that he destroys this temple when he demolishes the city of Shechem (Judg. 9:46-49)–the very temple whose funds had been used to install him as king!

Archaeologists have uncovered a temple in ancient Shechem (see the photo above). The destruction dates to the 12th century BC, the same time period as Abimelech’s destruction described in Judges 9. A standing stone was also discovered, part of which is still standing. It is probably this stone which is referred to in Judges 9:6 which states that Abimelech was made king “beside the terebinth tree at the pillar that was in Shechem.” Some also believe that this may be the same stone mentioned in Joshua 24:26. Archaeologists have also uncovered a statue of Baal at Shechem providing firm evidence that Baal was worshipped there. For further information click on the following link: Abimelech at Shechem.

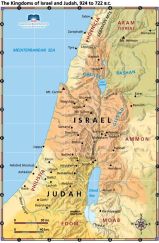

Shechem and The Divided Kingdom

The disappointing history of Shechem continues as it becomes the scene for the coronation of Solomon’s son Rehoboam (1 Kings 12:1). On this occasion, however, the northern tribes presented their grievances and when Rehoboam answered them harshly, the ten northern tribes made Jeroboam their king and created a permanent separation that lasted until the Exile. In fact, Shechem was fortified by Jeroboam and became the first capital city of the Northern Kingdom (1 Kings 12:25). If the reign of Abimelech emphasized the spiritual apostasy of Israel, the dissolution of the United Monarchy at Shechem was a precursor to the troubles that would plague Israel and Judah eventually leading both kingdoms into exile. Thus bringing to an end (at least momentarily) the promise made to Abram to give the Land of Canaan to his descendants.

The New Testament

By the first century A.D., the area around Shechem had become part of Samaritan territory. In fact, archaeologists tell us that Shechem ceased to exist in the first century B.C.. The only direct reference to the ancient city of Shechem is found in Stephen’s speech in Acts 7:16, when he is recounting the history of the patriarchs. However, the NT knows another very important episode that happened in the vicinity of ancient Shechem. This is the story of Jesus meeting a Samaritan woman at a well near Sychar (John 4:5). Whether Sychar refers to ancient Shechem or to a nearby town (known today as Askar), is disputed by scholars. One thing that is certain is that the well that Jesus meets this woman at is the well of Jacob and is near the parcel of land given to Joseph (John 4:5). Today a Greek Orthodox Church has been built over the site (see the photo on the left) which sits near the foot of Mount Gerizim. Anyone familiar with the ancient site of Shechem from the OT would immediately recognize that this conversation takes place in the same locale by the reference to the mountain on which the Samaritans worship (John 4:20). The ruins of the Samaritan Temple on Mount Gerizim can still be seen today. This Temple, built around the middle of the 4th century B.C., was destroyed probably sometime in the 2nd century B.C. (either by John Hyrcanus, or Simeon the Just).

While Jesus’ meeting with the Samaritan woman has many implications (including her own salvation, as well as those in the town), for our purposes it creates the perfect ending to the sorted tale of the city of Shechem. Jesus’ response to the woman at the well concerns worship that is “in Spirit and in truth” (John 4:23). How fitting that Jesus speaks of the meaning of worship that pleases the Father in a place where Abram and Jacob had built altars to the true God, and where Jacob and, later Israel, had put away their foreign gods in order to worship the God of Israel. How fitting also that Jesus brings the gift of the Kingdom of God to this woman and the people of her town in the very area that had witnessed the division of the Kingdom of Israel! Knowing the stories about Shechem in the OT and understanding that Jacob’s well and the first century village of Sychar is in this same geographical area brings a satisfying conclusion to a city with a mixed spiritual and political heritage. How good of God to bring this region full-circle through providing the living water that only Jesus can give!

For more on Shechem see the excellent article entitled: The Geographical, Historical & Spiritual Significance of Shechem at bible.org.