Important or Impotent: How Many Sons Did Absalom Have?

Did you know that 2 Samuel 14:27 states that Absalom had 3 sons, but in 2 Samuel 18:18 Absalom says that he has no son? In the previous article on Absalom’s hair I pointed out this apparent contradiction and promised to offer an explanation. The easiest way of explaining away the contradiction (frequently suggested by commentators) is that Absalom’s sons must have died prematurely. I believe this whitewashes the problem (the text gives no hint that the sons died) and obscures what the biblical author is seeking to accomplish.

Writing Technique in 1&2 Samuel

The author(s) of 1&2 Samuel seems to be fond of using inconsistencies in the story as a literary technique that causes the reader to pause and reconsider something stated earlier in the narrative. There are numerous examples of this, but perhaps the best is when Saul was commanded to wipe out Israel’s enemy, the Amalekites (1 Sam. 15:1-3).

Although the story makes clear that Saul is disobedient in sparing the king of the Amalekites, Agag (15:9), he appears to be the only human survivor. Subsequently, he is put to death by Samuel (15:33), which seems to put an end to all of the Amalekites. However, in the chapters surrounding the death of Saul, we are not only reminded that he was disobedient by not wiping out the Amalekites (1 Sam. 28:18), but Amalekites appear all over the place! (1 Sam. 27:8; 30:1-18; 2 Sam. 1:8, 13). This often puzzles readers, and may appear contradictory. In fact, it is a masterful way of surprising the reader and driving home the message that Saul was far more disobedient than we realized!

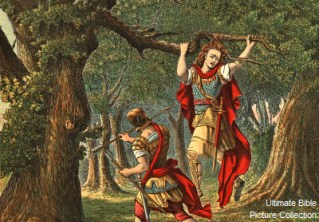

This same writing technique is at work in the two statements about Absalom’s sons (or lack thereof). The first important observation is to notice where these statements occur. The author uses the two statements about Absalom’s children (2 Sam. 14:27; 18:18) to bracket the account of Absalom’s rebellion. As discussed in the last article, the notice about Absalom’s hair and children, is a statement of power and virility. It causes the reader to think of him as a mighty warrior and a formidable foe. The second statement (“I have no son”) occurs immediately after Absalom’s death and burial, and metaphorically reveals the truth of the matter: Absalom was not a mighty warrior, nor a real threat to the kingdom. He was not as important as he appeared; in fact, he was impotent.

Isn’t There Still a Contradiction About How Many Sons Absalom Had?

While this might seem like a plausible explanation as far as the literary technique goes, it still leaves the obvious questions: so exactly how many sons did Absalom have, and aren’t the two passages still contradictory? The answer to these questions is found in examining the two texts carefully. 2 Sam. 14:27 is an objective statement by the biblical narrator that Absalom had 3 sons and 1 daughter. A fundamental rule of biblical interpretation is: you can trust the biblical narrator because he always tells the truth (see my book Family Portraits, p. 9 for a brief discussion on this point). Therefore, we can be confident that Absalom did indeed have 3 sons and 1 daughter.

Notice, however, that the statement about having no son in 2 Sam. 18:18 is not made by the narrator, but by Absalom himself. Could Absalom be wrong? This hardly seems likely. Absalom would surely know how many sons he has, and so would all who know him, therefore, this too must be an accurate statement. But if the narrator and Absalom contradict each other, how can they both be right? I suggest we are asking the wrong question. The important question is not “how many sons,” but rather, at what time in his life did Absalom make this assertion? Although the narrator puts this statement after Absalom’s death and burial, it is clear that it happened at some point in Absalom’s past. The author is merely reporting it posthumously. 2 Sam. 18:18 is actually very vague about when Absalom uttered these words. It simply says, “in his lifetime.” In other words, Absalom’s statement is taken from some unspecified time in his life. The statement should not be viewed chronologically, as if it had to have occurred after the observation in 2 Sam. 14:27. This can mean that when Absalom initially uttered it, it was true. In fact, it is obvious from this statement that Absalom used having no son as a justification for erecting a monument to himself. Later on, however, he fathers 3 sons and a daughter. So Absalom ends up with the best of both worlds: He gets a monument to himself plus, later on, 3 sons and a daughter!

This recognition reveals the hypocrisy of Absalom. A character study demonstrates that he is a master at making things appear other than they really are (see chapter 24 in Family Portraits).

The biblical author cleverly captures this by taking Absalom’s statement about not having a son out of its chronological context (which he tells us he is doing by the statement, “in his lifetime”) and putting it at the end of his life. The reader notices the contradiction between 14:27 and 18:18 and, by carefully examining the passages, concludes that Absalom is not what he appears to be. Absalom’s humiliating death and burial become conclusive proof of this fact, and all those who were beguiled by his charm and good looks now appear foolish. The message is sobering: we may be able to mask who we really are for awhile, but at some point, whether in life or in death, the truth will ultimately be revealed. Better to be honest and real while we live. Better to live with integrity, than to allow death to unmask the ugly truth about us. Thank heaven for a God who sees and accepts us just as we are, if we are only willing to remove the mask and let Him in.