Abel Beth Maacah: The Face of a King?

An exciting new discovery has recently been announced regarding the discovery of a small (2 inch/5 cm) sculpted head at Abel Beth Maacah. The discovery is exciting for at least two reasons. First, no human likeness like this has ever been discovered in Israel that dates to this time period. Eran Arie, the Israel museum’s curator of Iron Age and Persian archaeology states that it is one of a kind. “In the Iron Age, if there’s any figurative art, and there largely isn’t, it’s of very low quality. And this is of exquisite quality.” Second, the likeness appears to be that of a king. More on that below, but first, where is Abel Beth Maacah and what is its significance? (For a YouTube video that shows a fly-over of Abel Beth Maacah click here).

Location and Biblical Significance of Abel Beth Maacah

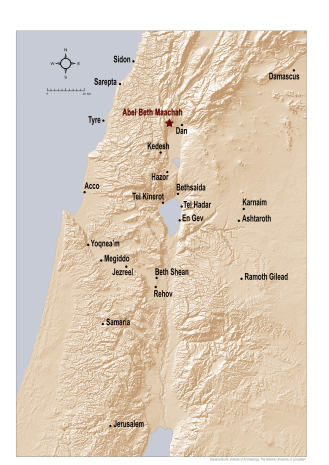

Abel Beth Maacah is located on the northern border of present-day Israel (bordering Lebanon), at the northern end of the Huleh Valley. This ancient tell, lies 4.5 miles (6.5 km) west of Tel Dan and a little over 1 mile (2 km) south of the modern town of Metulla. It is one of the largest tells (a little over 24 acres or 10 hectares), that remained unexcavated in Israel until a few years ago. Although this important archaeological site was initially identified in the 19th century as the probable site of ancient Abel Beth Maacah, an extensive survey of the mound was only conducted in 2012 with excavations beginning in 2013 under the auspices of Robert A. Mullins of Azusa Pacific University, Los Angeles and Naama Yahalom-Mack and Nava Panitz-Cohen of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. The site consists of a large lower mound on the south, a smaller upper mound on the north, and a moderately high “saddle” that connects them. Evidence of settlement begins in Early Bronze II and continues through the Iron Age (I & II), and includes the Persian, Hellenistic, Medieval, and Ottoman periods. Continuing into the modern era, an Arab village existed on part of the site until 1948.

The Bible refers to Abel Beth Maacah in three places. The first occurrence is found in 2 Samuel 20:14-22. Following Absalom’s revolt against David, a man by the name of Sheba son of Bichri attempts to draw Israel away from David. His rebellion is not nearly as successful as Absalom’s (which ultimately ends in failure also) as he retreats to Abel Beth Maacah. Joab, David’s commander, in hot pursuit besieges the city. A wise woman intervenes and saves the city by having Sheba’s head cut off and thrown over the wall. One of the interesting asides of this story is the wise woman’s characterization of Abel Beth Maacah as “a city and a mother in Israel” (v. 19). Furthermore, she claims that Abel was known as a place for seeking wisdom and ending disputes (v. 18). The wise woman’s words testify to the ancient significance of Abel Beth Maacah, which the size of the tell also suggests. The next mention of Abel is found in 1 Kings 15:20. It is this reference that may be the most significant regarding the discovery of the sculptured head. The story in 1 Kings 15 tells of Asa king of Judah asking for the help of Ben Hadad I of Syria (Hebrew–Aram) against his rival from Israel, Baasha. War had broken out between Asa and Baasha and it appears that Baasha had the upper hand. As Baasha fortified the city of Ramah (the prophet Samuel’s hometown)–a city only a few miles from Jerusalem–Asa sent treasures from the Temple to enlist the aid of Ben-Hadad. According to 1 Kings 15:20, Ben Hadad came against Israel and among the cities he attacked was Abel Beth Maacah. The head sculpture fits roughly within this period of time. We shall return momentarily to discuss the significance of this. Finally, Abel is also mentioned in 2 Kings 15:29 among a list of cities conquered by the Assyrian king Tiglath-pilesar III. As a border city (bordering the kingdoms of Israel, Aram, and Phoenicia), Abel was always vulnerable to attack by foreign enemies.

Is This a Royal Face and Can We Identify Him?

The sculptured head discovered in last summer’s excavation is made of faience, a glass-like material that was popular in jewelry and small human and animal figurines in ancient Egypt and the Near East. According to Yahalom-Mack, “The color of the face is greenish because of this copper tint that we have in the silicate paste.” There are several reasons why the archaeologists at Abel Beth Maacah believe this is the face of a Semitic king. First, the hair-do is very decisive for suggesting this is an ancient Near-Eastern king (see my article on the significance of Absalom’s hair and Niditch’s quote regarding hair here). Second, this is the way ancient Egyptian art depicts its Near-Eastern neighbors. Yahalom-Mack states, “The guy kind of represents the generic way Semitic people are described.” Third, the striped golden diadem that surrounds the head seems to clinch the idea of royalty. But who is this bearded wonder? Can archaeologists identify him?

The royal head has been dated to the 9th century B.C. There are two reasons for the dating. First, carbon dating has placed it in the 9th century B.C., but cannot pinpoint it more exactly. Second, after digging through the floor of a massive Iron Age structure, the head was found in the layer underneath dated to the 9th century B.C. Because, the head cannot be dated more precisely than sometime in the 9th century, and because Abel Beth Maacah was a border city and changed hands several times in the 9th century, it is not possible at present to identify what royal figure the head may represent. There are a number of candidates. If it is an Israelite king, the archaeologists suggest either Ahab or Jehu as possibilities. Because Abel was conquered by the Arameans during this time Ben Hadad I and his son Hazael are also candidates. Finally, because Abel was also on the border of Phoenicia and because Ahab was married to the infamous Jezebel (who was from the city of Tyre in Phonecia), her father, Ithobaal I is also considered a possibility. What is interesting about each of these candidates is that they are all mentioned in the Bible (1-2 Kings). Those excavating at Abel Beth Maacah remain hopeful that this summer season (2018) may reveal further evidence regarding this enigmatic (but exciting) find. Perhaps another part of the statue, or some other evidence will one day unravel the mystery. If further news comes to light, be sure that I will be informing the readers of this blog!

For other articles related to this discovery click here, here, here, and here.