2 Samuel 2–Asahel:Running into Trouble

Many people are unfamiliar with Asahel. He was the youngest brother of the more famous Joab, David’s army commander. Asahel only appears in one narrative, found in 2 Samuel 2. The story is about his vain pursuit of Abner, commander of Saul’s army, during the civil war between David and the house of Saul, resulting in his premature death. Asahel’s death is told in gruesome detail in 2 Samuel 2 and often leaves readers wondering why this story was related by the writer in the first place. The following post is an excerpt from chapter 20 of my book Family Portraits: Character Studies in 1 and 2 Samuel. In this chapter, I look at 3 men who shared several similarities: 1) they were all nephews of David and thus cousins; 2) they were all warriors; and 3) they all appear in limited roles in 2 Samuel. Although a first reading of Asahel’s death may leave the reader puzzled, a more careful examination reveals some important truths for all of us. I hope you enjoy this excerpt and consider purchasing a copy of Family Portraits for yourself or a friend. (For another excerpt from Family Portraits click here to read about Peninnah).

Asahel: Running into Trouble (2 Samuel 2:18–23, 30–32)

“Brave, impetuous, and ready to kill,” are the words we used to describe Abishai’s introduction in 1 Samuel. These same words are perhaps even truer of Asahel, proving him to be Abishai’s brother and a genuine son of Zeruiah. Together with Joab, all three brothers appear in 2 Samuel 2:18 in the midst of a conflict between Israel and Judah. The conflict was precipitated by Abner, who had marched his troops to Gibeon where he was met by Joab and “the servants of David” (2 Samuel 2:12–13). When an initial competition, also proposed by Abner, failed to produce a victor, the confrontation erupted into a full-scale battle, with Abner’s troops experiencing a sound defeat at the hands of David’s men (2 Samuel 2:14–17).

The victory, however, was not without great cost to the men of Judah. In a flashback of the battle, the author follows Asahel as he pursues Abner. The outcome of this altercation not only results in the death of Asahel one of Judah’s valiant warriors, it also sets the stage for a blood feud between Abner and the two remaining brothers (Joab and Abishai), culminating in the murder of Abner (2 Samuel 3:27, 30).

Asahel is described as one who is “as fleet of foot as a wild gazelle” (2 Samuel 2:18). It is Asahel’s running ability that provides the setting for the chase scene described in verses 19–23. However, Asahel’s greatest asset will prove to be his greatest liability––a liability perhaps hinted at in his description as a “gazelle.” While gazelles are fast and nimble, they are not known for their strength or predatory nature. Gazelles are not usually “pursuers” (v. 19): they use their speed to flee from danger, not to run towards it! What chance does a gazelle have if it pursues a battle-hardened warrior like Abner?

Furthermore, the word “gazelle” sounds a note of familiarity with a statement found in the previous chapter: “The beauty (gazelle) of Israel is slain on your high places! How the mighty have fallen!” (2 Samuel 1:19). The gazelle that David laments is probably Jonathan (see 2 Samuel 1:25) but could also include Saul. While Asahel’s equation with Jonathan may seem complimentary, it has an ominous ring to it. The previous gazelle (Jonathan) had been slain and had fallen in battle; likewise, Asahel the gazelle will soon be slain and “fall” in battle (2 Samuel 2:23).

The chase begins in earnest in verse 19. Two expressions characterize the dogged determination of Asahel. The first expression, “he did not turn to the right hand or to the left (vv. 19, 21), is language frequently used in Deuteronomy–2 Kings in reference to not deviating from the path of the Lord (Deut. 5:32; 17:11, 20; 28:14; Josh. 1:7; 23:6; 2 Kings 22:2). The second term is ʾaḥarē, occurring seven times in verses 19–23 and variously translated as “after,” “behind,” or “back.” It is also used frequently to express following “after” the Lord, or not following “after” other gods (Deut. 4:3; 6:14; 13:4; 1 Kings 14:8; 18:21; 2 Kings 23:3). Thus, Asahel’s pursuit of Abner uses language that articulates the resolve Israel should have in following the Lord. While pursuing the Lord leads to life (Deut. 5:32–33), Asahel’s single-minded pursuit of Abner ironically leads to his death (v. 23). An outline of 2 Samuel 2:19–23 demonstrates Asahel’s determination as it alternates between his pursuit and Abner’s warnings: Asahel pursues (v. 19); Abner turns and speaks (20–21d); Asahel continues his pursuit (21e); Abner speaks and cautions (22); Asahel continues (23a); Abner finally strikes (23b–d).

Still at some distance, Abner turns “behind him” to see Asahel hot on his trail (2 Samuel 2:20). Wishing to confirm the pursuer’s identity Abner calls out, “Are you Asahel?” to which Asahel responds with one breathless word, “I.” It is the only word he speaks in the entire narrative, highlighting his resolute focus on pursuing his prey. He is not interested in conversation; he is interested in catching Abner. As his name implies, Asahel is all about “doing” (“God has done,” or “made”) rather than talking. The doing, however, seems to have little to do with God and more to do with Asahel himself. Hence, Asahel’s answer, “I,” takes on a deeper significance.

Although the language is reminiscent of one pursuing God, the fact is that Asahel is in pursuit of his own glory. What could bring greater honor to a soldier than to kill the commander of the enemy’s army? This quest not only makes Asahel mute, but also deaf to the sound advice Abner tries to dispense. Using language that parallels the narrator’s, Abner says, “Turn aside to your right hand or to your left, and lay hold on one of the young men and take his armor for yourself ” (2 Samuel 2:21). This is Abner’s way of telling Asahel to pick on someone his own size, or, in other words, to take on someone of his own skill level and not to tangle with a more experienced soldier like himself. Asahel is undeterred.

Next, Abner is more direct and makes Asahel aware of the deadly consequences he will face if he does not cease his pursuit: “Why should I strike you to the ground? How then could I face your brother Joab?” (2 Samuel 2:22). Abner interjects an emotional element into his plea (“your brother Joab”), hoping it will slow down the fleet-footed Asahel. The advice, threats, and emotional pleas are all to no avail, however, as the narrator reports, “He refused to turn aside” (2 Samuel 2:23a). It is the last decision he will ever make, and it is a deadly one.

Winding Up on the Wrong End of the Stick!

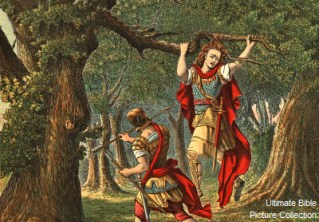

Asahel will not stop himself, so Abner must stop him. So far, Abner’s rhetoric has not caused his thick-headed opponent to “get the point.” Ironically, he will also not get the point of Abner’s weapon. Instead, with a thrust of the back end of his spear, Abner brings Asahel’s pursuit to an abrupt halt as the spear travels through his abdomen and proceeds out of his back (2 Samuel 2:23). It is ironic that with one blow of his spear, Abner did to Abishai’s brother what Abishai had wanted to do to Saul (1 Sam. 26:8). Asahel’s pursuit of glory causes him to “wind up on the wrong end of the stick.” Abner’s military prowess is so superior that it is not even necessary for him to assume the normal fighting posture of facing his adversary. This accords Asahel no respect. His death appears foolish and needless. Indeed, David’s lament over Abner in the next chapter (2 Samuel 3:33) could well have been sung over Asahel: “Should [Asahel] die as a fool dies?”

Asahel is the first of four characters to be stabbed in the abdomen in 2 Samuel. The first and the last (Amasa) to experience this fate are of the house of David, while the middle two (Abner and Ish-bosheth) are of the house of Saul, forming a deadly chiasm within 2 Samuel. Later in this chapter we will notice that the wording of Amasa’s death evokes images of Asahel’s, adding irony to the gruesome inclusio formed by their demise.

The conclusion of the battle underscores an important difference between Asahel and his brother Joab. After Abner pleads with Joab to, “return from following after his brothers” (2 Samuel 2:26—my translation), verse 30 informs the reader, “Then Joab returned from following after Abner.” The use of “after” reminds us of Asahel’s pursuit of Abner, and highlights Joab’s wisdom. Joab knows when to stop pursuing; he will wait for a more convenient opportunity. The contrast between the two brothers is stark. The body count for Judah says it all: nineteen men plus Asahel—the man who did not know when to quit. Asahel’s pursuit leads to a tomb in Bethlehem, while the wiser Joab lives to fight another day (2 Samuel 2:32).

Conclusion: Stop and Listen

The honor paid to Asahel by listing him first among David’s Thirty mighty men (2 Sam. 23:24) does not diminish the unnecessary tragedy of his death. Asahel proves himself to be much like his brothers: impetuous, hard, stubborn, and preferring violence to diplomacy. The one valuable quality of his brothers that he desperately lacks is discernment. McCarter rightly observes of Asahel that, “[He] appears in the present story as one so headstrong that he will not listen to reason even to save his own life.”

The Hebrew Scriptures frequently associate the act of listening with following the Lord. They are full of exhortations to listen, hear, heed, etc.; and the Scriptures record the consequences of those who do not (e.g., Exod. 15:26; Lev. 26:14–39; Judg. 2:17; 1 Sam. 15:22). Although Asahel’s story is not directly about listening to the Lord, the formulaic language used in the story recalls the frequent exhortation in Scripture to follow the Lord. Asahel’s wrong-headed pursuit took him down the enemy’s path and far from the safety of his comrades. Likewise, our pursuit of our own selfish goals can take us down the wrong path and lead us far from the safety of God’s people.

The Hebrew Scriptures frequently associate the act of listening with following the Lord. They are full of exhortations to listen, hear, heed, etc.; and the Scriptures record the consequences of those who do not (e.g., Exod. 15:26; Lev. 26:14–39; Judg. 2:17; 1 Sam. 15:22). Although Asahel’s story is not directly about listening to the Lord, the formulaic language used in the story recalls the frequent exhortation in Scripture to follow the Lord. Asahel’s wrong-headed pursuit took him down the enemy’s path and far from the safety of his comrades. Likewise, our pursuit of our own selfish goals can take us down the wrong path and lead us far from the safety of God’s people.

In one sense Asahel’s real-life tragedy becomes an analogy and warning to the nation of Israel, who often stubbornly chose to follow their own way (2 Kings 17:13–14) and closed their ears to God’s word and the way of wisdom (Isa. 6:10; Jer. 5:21). The same attitude is vividly portrayed in the New Testament, when members of the Sanhedrin refused to listen any longer to Stephen’s words. Luke reports: “Then they cried out with a loud voice, stopped their ears, and ran at him with one accord” (Acts 7:57).

Of course the story of Asahel is not just a warning to Israel, but to anyone who stubbornly pursues their own agenda while ignoring the wisdom of God and others. The grisly account of his death demonstrates how vain the all-out pursuit of glory is. If Asahel had stopped to consider Abner’s warnings, then he would not have been stopped by Abner’s spear. The message is clear: a stubborn refusal to stop and listen to good advice may have deadly consequences.