Mahanaim: Insights From Biblical Geography

Mahanaim is certainly not a household word. Even if you are a student of the Bible it may not be a familiar place to you. Don’t feel bad, my spell corrector doesn’t recognize it either! In spite of its relative obscurity, Mahanaim is an excellent example of important lessons that can be learned when biblical places are traced through the Bible (as advocated in my previous post Using Geography to Study the Bible). Mahanaim is mentioned thirteen times in the Bible (Gen. 32:1; Josh. 13:26, 30; 21:38; 2 Sam. 2:8, 12, 29; 17:24, 27; 19:32; 1 Kgs. 2:8; 4:14; 1 Chron. 6:80; and possibly Song of Songs 6:13). As this list shows, nearly half of the references occur in 2 Samuel.

Mahanaim in Genesis 32

The first occurrence of Mahanaim occurs in Genesis 32:1 in the story of Jacob’s return to the land after having spent 20 years with his uncle Laban in Haran (located in modern Syria). Jacob had fled to Haran because of his brother Esau’s threat to kill him for stealing the blessing from their father Isaac (Gen. 27:35-45). Jacob was fearful and apprehensive on his return, wondering if his brother still desired revenge (Gen. 32:6-7). The word “Mahanaim” is a dual form of the Hebrew word “Mahaneh,” which means “camp.” Therefore, Mahanaim means “two camps.” The meaning of this word is played on throughout the text. In Genesis 32:7 we are told that Jacob divided his family into two camps, hoping that if Esau attacked one part of the family, the other might escape (Gen. 32:8). The idea of two camps is also played upon by the mention of “God’s camp” which refers to Jacob’s encounter with some angels as he enters the land (Gen. 32:1-2). Jacob’s camp and Esau’s camp is yet a third reference to the idea of two camp’s in the story. The main point of this story, which extends into Genesis 33, is the reconciliation of two estranged brothers. The emphasis on two camps throughout suggests division and estrangement, but Esau’s warm and gracious welcome of his brother Jacob (Gen. 33:4), brings this reunion to a happy conclusion.

God’s place in the story is noted, not only through the mention of God’s camp (32:2), but also in Jacob’s wrestling with the Angel (Gen. 32:24-32). During this wrestling match, which happens at a place Jacob names Peniel (face of God–more on this below), Jacob receives a new name (Israel), which is suggestive of the change that has taken place in him. The theme of brother reconciled to brother in the sight of God is brought together in Jacob’s statement in Genesis 33: 10: “I have seen your face as though I had seen the face of God.” The word “face” occurs throughout Genesis 32-33, sometimes referring to God (as in Peniel) and other times referring to Esau. The point of this story can be summed up in a statement made by the apostle John in another context where he writes, “If anyone says, ‘I love God,’ and hates his brother, he is a liar; for he who does not love his brother whom he has seen, how can he love God whom he has not seen? And this commandment we have from Him: that he who loves God must love his brother also” (1 John 4:20-21).

Mahanaim in the Books of Joshua and Samuel

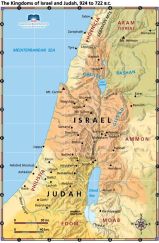

Mahanaim is not connected with any particular story in the Book of Joshua, but we do learn several important things about it. First, it was located on the border of the tribes of Gad and Manasseh (Josh. 13:24-30–Recall that Gad, Reuben, and 1/2 the tribe of Manasseh settled on the eastern side of the Jordan). Joshua 21:34-42 also informs us that it was a Levitical city, as well as a city of refuge.

2 Samuel contains two important stories in which Mahanaim plays a key role. Both stories in 2 Samuel concern a civil war within Israel. In 2 Samuel 2 David becomes king in Hebron of Judah, but rather than unite the kingdom under David, Abner (the commander of Saul’s army) takes Ish-bosheth (Saul’s son) and makes him king in Mahanaim (for more details on this story see my post here, or check out my book Family Portraits chapters 11 & 12). Abner and Ish-bosheth’s move to Mahanaim is probably a strategic one. It puts some distance between them and the Philistines (who have taken over a lot of Israelite terrritory–1 Sam. 31), and it also puts distance between them and David. The Lexham Bible Dictionary also suggests two other advantages: 1) It was in close proximity to Saul’s closest allies (the people of Jabesh-Gilead; see 1 Sam. 11); and 2) it gave them control of the iron ore industry which this area was famous for.

Mahanaim becomes important later again in 2 Samuel chapters 15-19, when David’s son Absalom rebels again him. Ironically, Absalom has himself proclaimed king in Hebron (where David was originally anointed), and when he marches on Jerusalem, David flees to–you guessed it–Mahanaim. Eventually David’s forces defeat Absalom and David returns to take up the throne again in Jerusalem. But it is in the chamber over the gate in Mahanaim where the memorable scene of David weeping for his slain son occurs. There we read of his gut-wrenching grief over the death of his son as he cries out, “O my son Absalom–my son, my son Absalom–if only I had died in your place! O Absalom my son, my son!” (2 Sam. 18:33/Hebrew text 19:1).

When one recalls the story of the reconciliation of brothers at Mahanaim told in Genesis 32-33, the sad stories of 2 Samuel become even more poignant. Both stories about civil war in 2 Samuel emphasize important family language and connections. When Joab pursues Abner and the forces of Israel in 2 Samuel 2 after inflicting a severe defeat on them, Abner pleads, “Shall the sword devour forever? Do you not know that it will be bitter in the end? How long will it be then until you tell the people to return from pursuing their brethren?” (2 Sam. 2:26). Notice the key word “brethren.” This is not simply a battle between two enemies; it is a family battle between brothers of the tribes of Israel. This same tragic message is enhanced further when David’s own son rebels against him. When the dust settles there is no victory celebration for David, but only the anguished cries of a father bereft of his son. The legacy of Mahanaim has turned from the shining legacy of brothers reuniting under God, to the nation of Israel and the family of David torn apart by hatred and enmity. It is making the geographical connection in these stories that highlights this important theme.

The Remaining Occurrences of Mahanaim

As a way of summarizing the other occurrences of Mahanaim, the reference in 1 Kings 2:8 refers back to the story of Absalom’s rebellion, while the reference in 1 Kings 4:14 notes that it was the seat of one of Solomon’s districts (he had 12 in all). The mention of Mahanaim in 1 Chronicles 6:80 is another geographical list stating that it belonged to the tribe of Gad. Finally, the use of “Mahanaim” in Song of Songs 6:13 (Hebrew text, 7:1), seems to be a reference to a particular kind of dance. Therefore, it is uncertain whether there is a reference to the city here. Before concluding this article, there is one more story we should look at.

Peniel, Succoth and Gideon

Although Mahanaim is not specifically mentioned in the story of Gideon, Peniel and Succoth are. We should recall that when Jacob prepared to meet his brother Esau, he was at Mahanaim. However, he wrestled with the Angel at Peniel close by. After reconciling with his brother, Genesis 33:17 tells us that Jacob moved on to Succoth. Being aware of this information demonstrates another way in which a knowledge of biblical geography (and biblical stories) can aid us in interpretation. In the story of Gideon, following his initial victory over the Midianites, he continues to pursue two of their kings. His pursuit takes him across the Jordan River into Gilead and the cities of Peniel and Succoth (Judg. 8:4-9). There he asks for supplies to feed his hungry and tired army, but the men of Peniel and Succoth refuse to help. Gideon states that upon his victorious return, he will deal with the men who have refused to support him and his troops. When Gideon does return victorious, he takes 77 elders of the town of Succoth and “teaches them a lesson” with thorns and briers. He then proceeds to Peniel (also spelled “Penuel”) and tears down a tower in the city, killing the men of the city. This is yet another tragic story related to this area that had begun with the reconciliation of brothers and the reconciliation of Jacob with his God. Here again we have fellow-Israelites who do not get along. The men of Succoth and Peniel refuse to support Gideon and in return he takes vengeance on them! So ends another sad story of disunity among brothers, who fail to see that they are each a reflection of the image of God and should, therefore, treat one another with loyalty and faithfulness. However, once again, it is the geographical information that links all of these stories together–stories with a common theme. The stories about Mahanaim (and the surrounding region) are just one example of how biblical geography can give us deeper insight into the Scriptures.